Okay, so there's nothing about this video that isn't cute. And that's fine. But what does it have to do with Lean?One of the most important lessons that Lean can teach us is how to appreciate variation and make the most of it.When Jim Henson and this little girl went on set, it was to create a product - an item of value. The task, as originally written, was to create a short video where Kermit and the little girl sang the English alphabet. A simple progression of 26 letters. So simple that variation was inconceivable and no other product was possible.But little girls do not have SixSigma Black Belts or PMI certification (thank heavens!).So the cameras roll and the little girl suddenly becomes a point source in variation, undermining the original scope of work and putting the project in danger. She keeps injecting "Cookie Monster" in the alphabet, as if he were a letter in the English Alphabet.Cookie Monster is not a letter in the English Alphabet.The little girl thinks this is very funny. Kermit does not, because Kermit is a project manager locked into one irreversible type of value.Jim Henson, operating Kermit, knows that he can use rewards and penalties to get the product he wants. He knows that the little girl is really excited to be there with Kermit and that taking Kermit away will get her to settle down and sing the alphabet. So Kermit storms off.But rather than saying "Kermit, come back, I will sing the alphabet!" this little girl finds the true value - the honest value - and says with a sincerity that anyone can admire:"I love you!"And, even in the video, you can actually feel the impact this had on Jim Henson. Another day at the office turned into a beautiful gift.All because of variation.The real beauty here is that even though this product was fundamentally broken - fundamentally it did not achieve its initial goal - Jim and the people at Children's Television Workshop thought this lesson was worth sharing. They saw that through variation in their youngest of knowledge workers, there was innovation and inspiration.There was value in variation.

The Lean Muppet Series: Introduction

I am 46 years old (at the time if this writing, it would be kind of nice to just keep on being a healthy active 46 year old, though).Being 46 year old and American, I was raised by three parents: Don and Jennifer Benson...and Jim Henson.Like most kids when I was growing up, I lived with Muppets. On Sesame Street, on the Muppet Show, in the Muppet Movie, even on Saturday Night Live a few times. Muppets like Kermit, Ernie, Bert, and later Yoda are as much a part of my generation's psyche as anything can be.But as we've aged, we seem to have lost sight of Jim Henson's vision, his message, and his passion. In this Lean Muppets series, I hope to re-introduce a lot of us to Jim's message and show how we might either learn from or be actually living out some classic Muppet skits every day.This series is for everyone who works in an office, has an idea, follows Lean / SixSigma / 5s / Lean Startup / Personal Kanban / Kanban for software development / Lean medicine / Lean government...you see how adults complicate things?This series is for everyone who feels dissatisfied, but would rather not.This series is for people wondering why their business is broken, and who are tired of non-Muppets telling them why.In a recent (April 2012) interview with iSixSigma magazine, I was asked what I thought Lean was all about. I talked about Deming's Theory of Profound Knowledge. (I will post a link when it is published).When I thought about this a few days later while enjoying a bout of jetlag in a Swedish Hotel, I realized that Deming's vision was Jim Henson's vision...and it's a vision I too share.To engage my hubris muscle, I will now say what I believe that distilled shared vision is:

If we care, we create.

If we create, we improve.

If we improve, we live.

That is my vision. That is Lean. That is Muppets.How to implement the vision? Here come the guides (updated as they come out over the next month):

Failure Demand and Unthoughtful Production:Lean Muppets Post 2

Sunk Cost, Loss Aversion, and Cannibalism: Lean Muppets Post 3

Disclaimer: Jim Henson and the Muppets are a global treasure that we all share in the legacy of. We learned to count, spell, cooperate, and respect each other through Jim's work. Modus Cooperandi and Personal Kanban have no legal relationship with the Muppets, but we sure were influenced by their wisdom.

Depth in Progress: of Wine Snobs, Audiophiles, and Agilistas

“Wine is to enjoy, not to judge.”~ Hwi Woong Jeong (웅가) Wine Enthusiast

The gentleman next to me took out his laptop and began typing, he had a large pile of wine labels and a notebook filled with wine notes. He began systematically copying them into his laptop. I figured he was a wine critic.Other work he went on to do involved software development and airplanes so my curiosity overtook me and we began to talk. It turned out that he was a software developer that worked with airplanes. But … he was also a noted wine critic enthusiast. He had been to the Pacific Northwest of the US on a wine excursion as a guest of the major wineries. He had been all over Washington and Oregon tasting.When I was in my 20s, I decided I wanted to be a wine snob. So I went and took courses on wines, read books, and started a collection. I became rather good at it. So good, in fact, that I found I wasn’t actually enjoying wine any more. I was always critiquing it. I could always find something not quite right.I told him this and he smiled and said, “wine is to enjoy, not to judge.”We will always suffer from snobbery – to this day, I cannot listen to music from laptop speakers. And I know more than my share of agile adherents who actively hate every team they come into contact with because of their flaws.We tend to fall in love with our ideas and nothing kills romance like familiarity. Richard Dawkins once said, “There is an anaesthetic of familiarity, a sedative of ordinariness which dulls the senses and hides the wonder of existence.”We do this all the time with our work. We get excited about a task or an idea and we go deep. Too deep. Beneath the layer of effort that separates excitement from boredom. From energizing to draining. From inspiration to drudgery.We might call this “depth in progress”. Just like we can have too much work in progress, we can also have too much depth. It’s simply doing too much of something. We go beyond what would be an acceptable level of completion and strive for “perfection.”

“The fact of storytelling hints at a fundamental human unease, hints at human imperfection. Where there is perfection there is no story to tell.” ~Ben Okri

At some point on the path to perfection, we pass the point of diminishing returns. After that point, our efforts do not return profit, only waste. In our pursuit of perfection, we identify all the things that cannot be perfect and then strive to perfect them. Yet, the imperfect is always with us. It is where growth resides.Yet the need for growth, and the imperfection, will always be there. We end up in a doom loop of reductio-ab-absurdum – we manage our products as if the end product were a fine diamond that would last centuries. Well, it took the planet millions of years to make that diamond, and we don’t have that kind of time.Therefore we need to approach our work by asking, “What is the least amount I can do to make this task successful?” In doing this, we want to move our ticket to DONE and have it stay there. No re-work, no additional tasks created because it was incomplete.Can that task be improved in the future? Absolutely. But for now, it is complete. We launch it, watch it work, and come back to improve upon it later if necessary.We want to know what the minimal completed task looks like and then do that. Anything beyond is too much work. Our previous goal of “perfect” is still valid, but now it has an upper boundary. Overly polishing the task does no one any good. Because of this, perfection is no longer gilding the lily - we now recognize the lily is perfect. We want to enjoy our wine, not judge it.

"To gild refined gold, to paint the lily ... is wasteful and ridiculous excess." ~ Shakespeare

One Day’s Idea is Another Day’s Waste

On my travels through startups and the corporate world I see small to gross acts of negligence. They usually come in the wrapper of something like, “because that’s our process.” Metrics are gathered for the sake of reports no one acts on. Information is collected to feed otherwise ignored databases. People fill out forms to protect the company from a long-forgotten infraction.Policies and processes we adopt over time are corporate inventory. We have to maintain them, administer them, and be annoyed by them. All these actions are waste.The tricky thing here is that all policies can be defended by “what if” arguments. “We can’t get rid of that policy … what if someone does something bad?”Well, what if someone does something bad? How likely is that to occur?We know for certain that the waste is making the group less effective when subjected to the policy. What is the likelihood of your What If?A gross example of this is airport delay post 9-11. The 9-11 hijackings had nothing to do with airport screening points. They were a systemic breakdown (and a highly improbable one) of the global intelligence network. Yet, the 631,939,829 people who flew in 2010 all were delayed at least one hour by needing to get to the airport early, stand in line, and subject themselves to security policies. At about 40,000 as an average income, this quickly pencils out to about 12.5 billion dollars worth of delay every year. That delay can be easily compounded by the lost time of collaboration that people have endure by leaving the office early.The What Ifs here are obvious. But so are the costs. Are there better ways of dealing with terrorist threats than incurring billions of dollars in passenger delay?Other examples are regular reports that show the progress of various business metrics. One company we visited generated a weekly report of dozens of pages and nearly 100 metrics every week. Not only did report generation take more than a combined 40 hours to produce (an obvious cost), it delayed the very projects it was trying to measure. In the end, the overwhelming number of charts, graphs, and numbers created a culture of managing by the numbers while totally ignoring what was really happening. Managers would comb through the document until they found the metric or two that went in the wrong direction, then they’d come to find out why.More often than not, the why was a normal fluctuation in the number. The conversation was waste, the “analysis” was waste, and the generation was waste. But those receiving the report had become so fixated on it that they couldn’t see beyond it. “What if we didn’t have this report? We’d never know what was going on!”Examine your policies regularly. Make sure that you don’t have policies to create waste. Photo by Anders V

Mozart’s Record Store: Personal Kanban Anti-Pattern 2: Only One Value Stream

I will not be accused of burying the lead here and say right up front:

Your Value Stream Is Wrong

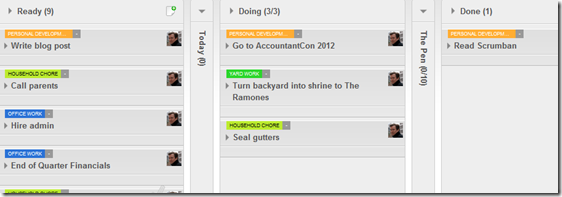

And it always will be.This is a good thing, as we work from day to day the steps we take to complete work subtly or even violently change. When we move from home to work to a special project, there are subtle and important differences to how we do what we do.Today’s anti-pattern is is painful to watch. When people fall into a certain way of visualizing their work or a certain value stream, it becomes comfortable to them. So comfortable, in fact, that they are reluctant or downright resistant to change or improve it. They then flounder in increasing painful work because their value stream doesn’t match their actual needs.Let’s say for example that Mozart is the manager of a record store in Bavaria. He has three main types of work over a given month. One is order new stock from a variety of suppliers. The second is make sure the books are in order. The third is … everything else.Everything else is actually easy - even though it may be rather chaotic at times. We visual this type of work with a standard Personal Kanban value stream of READY | DOING | DONE. The work is going to be varied and extremely task-focused. Each of Mozart’s tasks is its own element of value. The best way to manage this work, to weigh these options, and to get these tasks completed is in a model that accepts the complexities and inherent chaos of day-to-day work.However, in other more project centered types of work, he may get more from value streams geared toward tracking of that specific work or project.For example, when ordering stock, the ideal world would tell you that orders are placed and received each month at set times. Mozart’s store has a mix of goods provide through suppliers ranging from large vendors to one person in their basement. Order responses are highly varied, leaving Mozart having to track not only the rate at which inventory is sold, but also the average response times for ordering popular items.So here we see Mozart’s order processing kanban. The value stream is quite specific to the value created. This is repeating value created in a fairly predictable way. If Mozart was only using the READY | DOING | DONE value stream for this type of project, he would have dozens of tasks polluting the rest of his work. The stages in these value streams may not actually be tasks. So, say he finds it’s time to order a new set of Buddha Machines - so he contacts the people in China via email. When he does that he can move the Buddha Machine ticket to ORDER. A few days later, they might send him a letter saying, “We received your order and will get to it soon.” Mozart can then move the ticket to CONFIRMED - even though he really didn’t do any task himself. The point here is that there is new useful information about the state of the Buddha Machine order. A few days later, he gets an e-mail saying that the Buddha Machines have shipped. Mozart again can move the ticket.From time to time, new tasks may appear in Mozart’s regular Personal Kanban that say things like “Order new AxMxAx album”. At that point, when Mozart does do the ordering, he will move that ticket to done, but also start a new ticket in the order processing kanban.So, here we see that Mozart’s work can have more than one value stream.Now, let’s say this works for Mozart for a while, but he begins to notice that even after he receives confirmation many orders are not shipped. Tickets start to back up at the “ordered” stage but don’t progress beyond. Mozart can then come up with ways to fix that problem. For example, he could insert a “remind vendor” column that he can move tickets to if they aren’t shipped in less than a week.Mozart must change his value streams to meet his needs. So must we all.